AoIR 2021

'Fake News' on Facebook: A Large-Scale Longitudinal Study of Problematic Link-Sharing Practices from 2016-2020

Dan Angus, Axel Bruns, Edward Hurcombe, and Stephen Harrington

- 12-16 Oct. 2021 – long version of a paper presented at the Association of Internet Researchers conference, online

- presented as part of a panel on “'Fake News' and Other Problematic Information: Studying Dissemination and Discourse Patterns”

Video of the Presentation

Presentation Slides

Paper Abstract

Introduction

‘Fake news’ has been one of the most controversial phenomena of the past five years. Usually referring to overtly or covertly biased, skewed, or falsified information, the term has become a byword of what some see as a new, polarised, ‘post-truth’ era. ‘Fake news’ was blamed for the apparently unexpected results of the 2016 Brexit vote as well as the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Booth et al., 2017), and has continued to be held responsible for influencing and distorting public opinion against political establishments and minority communities around the world. Concerns have centred especially on the role of fringe and hyperpartisan outlets using major social media platforms such as Facebook to spread mis- and disinformation. Well beyond the ‘dark web’, such platforms now serve as hosts of and vectors for problematic information, spread by malicious actors with political and economic motives.

In response, researchers have begun to examine the dissemination of ‘fake news’ and other mis-, dis-, and malinformation (Wardle & Derakhshan, 2017) on such platforms, seeking empirical evidence to support or counter these concerns. However, such research has tended to focus either on specific news events, such as the 2016 U.S. election (e.g. Allcott & Gentzkow, 2017), on certain actors, such as state-backed disinformation campaigns (e.g. Bail et al., 2019), or on specific mechanisms of dissemination, such as the use of algorithms and automation in producing and disseminating false information (Woolley & Howard, 2017).

By contrast, there have been comparatively few comprehensive, systematic investigations of the dissemination of, and engagement with, ‘fake news’ at scale; fewer still have taken a longer-term, longitudinal approach. This is due largely to the considerable methodological challenges that such approaches face. This paper addresses this gap, presenting initial findings from major project that builds on and significantly advances previous work by conducting a large-scale, mixed-methods analysis of the empirical evidence for the dissemination of, engagement with, and visibility of ‘fake news’ and other problematic information in public debate on major social media platforms.

This first study centres on Facebook, examining link-sharing practices for content from well-known sources of problematic information. We draw on data from CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook; conduct a large-scale network mapping and analysis exercise to identify the key patterns in the dissemination network for ‘fake news’ content; and complement this analysis with computational and manual content analysis to identify the key thematic and topical patterns in different parts of this network.

Constructing the Problematic Link-Sharing Network

Drawing on several lists of suspected sources of ‘fake news’ that have been published in recent years by various scholarly projects (such as Hoaxy: Shao et al., 2016) and in the related literature (including Allcott et al., 2018; Grinberg et al., 2019; Guess et al., 2018; 2019; and Starbird et al., 2017), since 2016 we have compiled and iteratively updated the Fake News Index (FakeNIX), a masterlist of Web domains that have been identified as publishing problematic information.

We use this masterlist to systematically gather all posts on leading social media platforms that contain links to content on these domains, to the extent that the platforms’ Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) permit this; for Facebook, this utilises the Facebook-operated social media data service CrowdTangle. For ethical and privacy reasons, CrowdTangle is limited to covering posts on public pages, public groups, and public verified profiles only; it does not provide information on the circulation of FakeNIX links in private groups or profiles on Facebook, nor on URLs posted in comments. While this is a notable limitation, and our study can therefore only observe the public sharing of such content on Facebook, it is nonetheless possible to extrapolate from this to the wider private posting and on-sharing of such links in those Facebook spaces that we are unable to observe directly.

We thus use the current list of 2,314 FakeNIX domains to gather all posts from public spaces on Facebook that contained links to content on these domains and were posted between 1 Jan. 2016 and 31 Dec. 2020; this process is ongoing at the time of submission, and expected to result in a dataset of several tens of millions of public Facebook posts.

From these, we intend to construct two bipartite networks that connect Facebook pages and groups to the URLs they shared. These operate at two levels of specificity: the article level (taking into account the specific article URL, e.g. site.com/article.html), and the domain level (stripping the article details and using only the domain, e.g. site.com). The domain-level analysis will reveal which sites act as strong attractors for a diverse array of Facebook communities, or as central hubs for major clusters, while the more sparsely connected article-level network will enable us to examine the emergence of sub-networks that form around shared topical interests, such as specific conspiracy theories or ideologies. All graphs are constructed using the Gephi open-source graph modelling package (Bastian, Heymann, & Jacomy, 2009).

Further, the long-term longitudinal nature of our dataset provides an opportunity for us to repeat this analysis for distinct timeframes within the five-year period covered by our data. This will reveal the stable or shifting allegiances between Facebook communities and their problematic information sources, driven both by internal dynamics (such as ideological splits or interpersonal animosities) and by external developments (such as elections, scandals, or other news events).

Finally, we will complement this study of the network dynamics with additional computational and manual analysis of our data. This will highlight changes in the dominant themes of ‘fake news’ and other problematic information within our overall dataset, and within the specific clusters that emerge in our network of pages and content, and provide further explanation of the sharing dynamics observed over the five turbulent years covered by our dataset.

Preliminary Results

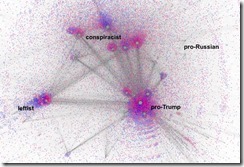

Fig. 1: Preliminary bipartite visualisation of networks between Facebook pages (blue) or groups (red) and a subset of the FakeNIX domains shared in their posts (grey), 2016-20

A work-in-progress analysis of a subset of the full dataset, covering a random selection of all FakeNIX domains, demonstrates the utility of our approach (fig. 1). At the domain level, the bipartite network between Facebook pages or groups and the content they shared reveals a distinct set of patterns. Central to the network is a cluster of Facebook pages and groups that frequently shared links to pro-Trump and/or far-right US outlets such as Breitbart, InfoWars, and RedState; to the left is a considerably smaller cluster of left-leaning pages and groups that frequently shared outlets such as Politicus USA or Addicting Info.

Above these hyperpartisan clusters, and substantially connected with both of them, are collections of pages and groups that frequently engage with conspiracist outlets such as GlobalResearch.ca, Collective Evolution, Activist Post, or Geoengineering Watch. To their right, and (in this incomplete dataset) as yet with limited connection to the major parts of the network, are foreign influence operations such as the Russian-backed RT and Sputnik News, and the Bulgarian-based Zero Hedge. There are also some notable differences in the use of Facebook platform affordances: leftist content and links to Collective Evolution appear to be shared more by Facebook pages (shown in blue), while pro-Trump content and most conspiracy theory materials are more likely to circulate in groups (red). It remains to be seen whether these trends hold true for the full dataset.

In our further work with the full dataset, we also intend to examine the longitudinal dynamics of these networks, with particular focus on how Facebook’s moderation approaches and other external interventions have affected the activities of specific clusters. We expect, for instance, that pandemic-related conspiracist content will emerge as a significant factor in 2020, alongside problematic content addressing the US Presidential election and its aftermath.

Acknowledgment

Data from CrowdTangle, a public insights tool owned and operated by Facebook.

References

Allcott, H., & Gentzkow, M. (2017). Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 31(2), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211

Allcott, H., Gentzkow, M., & Yu, C. (2018). Trends in the Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media. https://arxiv.org/abs/1809.05901v1

Bail, C. A., Guay, B., Maloney, E., Combs, A., Hillygus, D. S., Merhout, F., Freelon, D., & Volfovsky, A. (2019). Assessing the Russian Internet Research Agency’s Impact on the Political Attitudes and Behaviors of American Twitter Users in Late 2017. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1906420116

Bastian, M., Heymann, S., & Jacomy, M. (2009). Gephi: An Open Source Software for Exploring and Manipulating Networks. Proceedings of the Third International ICWSM Conference, 361–362. http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/09/paper/viewFile/154/1009/

Booth, R., et al. (2017, Nov. 15). Russia Used Hundreds of Fake Accounts to Tweet About Brexit, Data Shows. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/14/how-400-russia-run-fake-accounts-posted-bogus-brexit-tweets

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706

Guess, A., Nyhan, B., & Reifler, J. (2018). Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the Consumption of Fake News during the 2016 US Presidential Campaign. Dartmouth College. http://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/fake-news-2016.pdf

Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than You Think: Prevalence and Predictors of Fake News Dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau4586. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aau4586

Shao, C., Ciampaglia, G. L., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2016). Hoaxy: A Platform for Tracking Online Misinformation. Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Companion on World Wide Web, 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1145/2872518.2890098

Starbird, K. (2017, March 15). Information Wars: A Window into the Alternative Media Ecosystem. Medium. https://medium.com/hci-design-at-uw/information-wars-a-window-into-the-alternative-media-ecosystem-a1347f32fd8f

Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information Disorder: Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. https://shorensteincenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Information-Disorder-Toward-an-interdisciplinary-framework.pdf

Woolley, S. C., & Howard, P. N. (2017). Computational Propaganda Worldwide. Working Paper 2017.11. Oxford: Computational Propaganda Research Project. http://comprop.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/89/2017/06/Casestudies-ExecutiveSummary.pdf