AoIR 2022

Electioneering in Pandemic Times: The 2022 Australian Federal Election on Facebook and Twitter

Axel Bruns, Daniel Angus, Timothy Graham, Ehsan Dehghan, Nadia Jude, and Phoebe Matich

- 3 Nov. 2022 – Paper presented at the AoIR 2022 conference, Dublin

Presentation Slides

Abstract

Introduction

The 2022 Australian federal election campaign, between March and May 2022, takes place in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic – a period of time during which most Australian states and territories experienced severe disruptions from sometimes lengthy lockdowns; internal and external borders were closed to all but essential travel; and significant disagreements unfolded between state and federal leaders about appropriate public health, economic, and civil liberties responses to the immediate pandemic threat itself, to its impact on the economy, and to the spread of mis- and disinformation seeking to exploit the situation for hyperpartisan political benefit.

The conservative federal government by the Coalition of Liberal and National Parties under the leadership of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, in particular, has been widely criticised for its lack of forward planning, its misdirected financial support that benefitted major corporations rather that citizens, and its politicisation of policy differences between state and federal leaders (e.g. Glenday, 2022). Meanwhile, overshadowed by the public attention directed to state and territory leaders during the pandemic, the oppositional Australian Labor Party has struggled at federal level to clearly present an alternative vision for the country, with opinion polls still showing considerable uncertainty about the leadership credentials of opposition leader Anthony Albanese.

Such disenchantment with both major party blocs is exploited, in turn, by a wave of broadly centrist independent candidates seeking to win electorates previously held by conservatives and unlikely to elect Labor politicians; in addition, the populist United Australia Party under the leadership of controversial mining billionaire Clive Palmer has already begun an aggressive billboard, broadcast, SMS, and online advertising campaign that seeks to disrupt the conventional party landscape and is actively distributing COVID-19 disinformation (Taylor & Karp, 2021).

Tendentious electioneering and outright disinformation, related to COVID-19 as well as to other major issues, are also likely to feature in the major parties’ campaigns, however: in past elections, the Labor Party executed a successful ‘Mediscare’ campaign, worrying voters about supposed Coalition plans to wind back universal healthcare in Australia (Hunter, 2016); the Coalition won the 2019 election in part as a result of its ‘Death Tax’ campaign, misrepresenting Labor’s plans to reduce tax benefits for rich retirees (Emerson & Weatherill, 2019). Such campaigns are likely to find fertile ground in a fractious and frustrated electorate that is already affected by substantial volumes of COVID-19 mis- and disinformation.

Approach

Building on the methodology established in our studies of Australian federal elections in 2013, 2016, and 2019, this work-in-progress paper presents a first analysis of social media campaigning during the 2022 Australian federal election. For this we draw on our established approach to analysing Twitter campaigning (as utilised for our studies of the 2013, 2016, and 2019 campaigns; Bruns, 2017; Bruns & Moon, 2018; Bruns et al., 2021) and on our translation of that approach to the analysis of campaigning via candidate pages on Facebook (as developed for the 2020 Queensland state election; Bruns & Angus, 2020).

As part of an international collaboration to identify political candidates on social media platforms that has already produced a dataset of election candidates on Twitter for the 2021 federal election in Germany (Sältzer, 2021), we identify the Twitter accounts and Facebook pages of all Australian federal election candidates, and use the Twitter API and the Facebook data tool CrowdTangle to capture all posts by these accounts and pages, and all tweets directed at the candidate accounts on Twitter as well as interactions around the candidate pages on Facebook. We capture these throughout the election campaign, from the official issuing of the electoral writs to the election day.

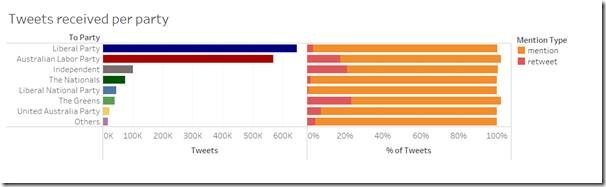

As in our previous election analyses, we draw on these datasets to produce a number of insights; as the 2022 election has yet to take place, we use examples from past elections to illustrate these here. First, we investigate the overall distribution of engagement with the different parties and their candidates. Such engagement commonly centres on the Liberal and Labor Parties as the most prominent Australian political parties, and here especially on their respective candidates for the Prime Ministership (see fig. 1 as an example of engagement with party candidates on Twitter during the 2019 election), but our longitudinal analysis of data from the past three elections shows that differences across election cycles point to the relative salience of the parties’ electoral messaging (Bruns et al., 2021).

Fig. 1: Engagement on Twitter with candidates in the 2019 Australian federal election

Second, we track such engagement across the campaign period. Here, we examine especially the utilisation of specific platform affordances (@mentions, retweets, quote tweets on Twitter; comments, shares, and reactions on Facebook) over time, in order to identify key campaign moments (leaders’ debates, policy releases, controversies) and determine the popular reaction they generated (see fig. 2 as an example of the dynamics of Facebook reaction sentiment for the major parties during one week in the 2020 Queensland state election). We further combine this with the computational extraction of major themes from the content gathered from both platforms, in order to correlate campaigning themes and voter engagement.

Fig. 2: Positive (love, care, haha, wow) and negative (sad, angry) Facebook reactions to candidate posts during one week in the 2020 Queensland state election

Finally, we also draw on a state-of-the-art detection toolkit to identify cases of coordinated behaviour in the dataset: these may include behaviours like coordinated posting, coordinated link-sharing, coordinated post sharing on Facebook or retweeting on Twitter, or coordinated commenting. Some such behaviours, in turn, may represent standard practice in social media campaigning (for instance as several party candidates post the same talking points, campaign memes, or news articles at the same time), while others may point to more covert and problematic activities (as party operatives or other actors engage in astroturfing or sockpuppeting in order to artificially inflate the visibility of specific topics). We engage in close reading and forensic analysis to investigate and assess such cases of coordinated behaviour.

This paper presents the insights emerging from these analyses, in the turbulent political aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. In this panel it is further complemented by a paper that specifically investigates political advertising practices on Facebook during the election. In combination, the papers provide a rich and timely analysis of social media campaigning and engagement during the 2022 Australian federal election.

References

Bruns, A. (2017). Tweeting to Save the Furniture: The 2013 Australian Election Campaign on Twitter. Media International Australia, 162, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X16669001

Bruns, A., & Angus, D. (2020). 2020 Queensland State Election: Week 1-4 Update. QUT Digital Media Research Centre. https://research.qut.edu.au/dmrc/2020/10/09/2020-queensland-state-election-week-1-update/, https://research.qut.edu.au/dmrc/2020/10/16/2020-queensland-state-election-week-2-update/, https://research.qut.edu.au/dmrc/2020/10/23/2020-queensland-state-election-week-3-update/, https://research.qut.edu.au/dmrc/2020/10/30/2020-queensland-state-election-week-4-update/

Bruns, A., Angus, D., & Graham, T. (2021). Twitter Campaigning Strategies in Australian Federal Elections 2013–2019. Social Media + Society, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211063462

Bruns, A., & Moon, B. (2018). Social Media in Australian Federal Elections: Comparing the 2013 and 2016 Campaigns. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 95(2), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018766505

Emerson, C., & Weatherill, J. (2019). Review of Labor’s 2019 Federal Election Campaign. Australian Labor Party. https://alp.org.au/media/2043/alp-campaign-review-2019.pdf

Glenday, J. (2022, 31 Jan.). Scott Morrison's Had a Bad Start to the Year. Can He Turn It Around? ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-01-31/scott-morrison-election-albanese-newspoll/100793354

Hunter, F. (2016, 5 July). Australian Federal Election 2016: Malcolm Turnbull Takes Full Responsibility for Campaign. Sydney Morning Herald. http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/federal-election-2016/australian-federal-election-2016-malcolm-turnbulltakes-full-responsibility-for-campaign-20160705-gpyx9z.html

Sältzer, M., Stier, S., Bäuerle, J., Blumenberg, M., Mechkova, V., Pemstein, D., Seim, B., & Wilson, S. (2021). Twitter Accounts of Candidates in the German Federal Election 2021 (GLES). Cologne: GESIS Data Archive. ZA7721. Data file version 2.0.0. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13790

Taylor, J., & Karp, P. (2021, 7 Sep.). Clive Palmer and Craig Kelly Using Spam Text Messages to Capture Rightwing Vote ahead of Election, Expert Says. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2021/sep/08/clive-palmer-and-craig-kelly-using-spam-text-messages-to-capture-rightwing-vote-ahead-of-election-expert-says